Learning by Inferring

Does your child read well but not comprehend what she's reading?

Does he read well and recall facts quickly, yet scores low on reading comprehension?

If your answer is yes to either of these questions, your child may have difficulty with inference while reading. What exactly does that mean?

A reader who isn't inferring is unable to connect the dots between the words on the page and facts presented in the text to the real meaning. They miss the intended message or "moral of the story" which is often not stated literally. This type of reader is skilled at pronunciation, reading aloud fluently, and recalling facts, but usually struggles with making rich, detailed images in their mind during the reading process.

To infer is to guess by reasoning or from the facts. It’s the ability to “read between the lines” in which the parts all become clues to the greater whole. A student who makes clear, accurate images can infer what the meaning of the story is, and make conclusions about the author’s message, even if the author didn’t state it out right. This is a vital part of comprehending what you read.

Visualizing while reading is key to developing reading comprehension and deep critical thinking in a manner beyond just recalling the facts. Based on the LindaMood-Bell ™ system of Visualizing and Verbalizing For Language Comprehension and Thinking, the student pauses after each sentence and verbalizes what they pictured. Verbalizing is a key component because it forces the student to organize their thoughts in a sequential way, what happened first, next, and last. Verbalizing helps the student to remember the pictures they made. Successful readers infer meaning based on what they picture in their mind while reading. They make a movie in their minds when they read, where one scene connects to the next scene. We can't see what someone is thinking or imagining when they're reading so it is difficult to detect this process in our children and students. If only we had x-ray vision glasses to observe the brain at work! We can only observe their struggle. Instead of viewing a "movie" in their mind while reading, students who struggle with comprehension make more of a “slide show”, a series of facts that don’t always connect to the next scene.

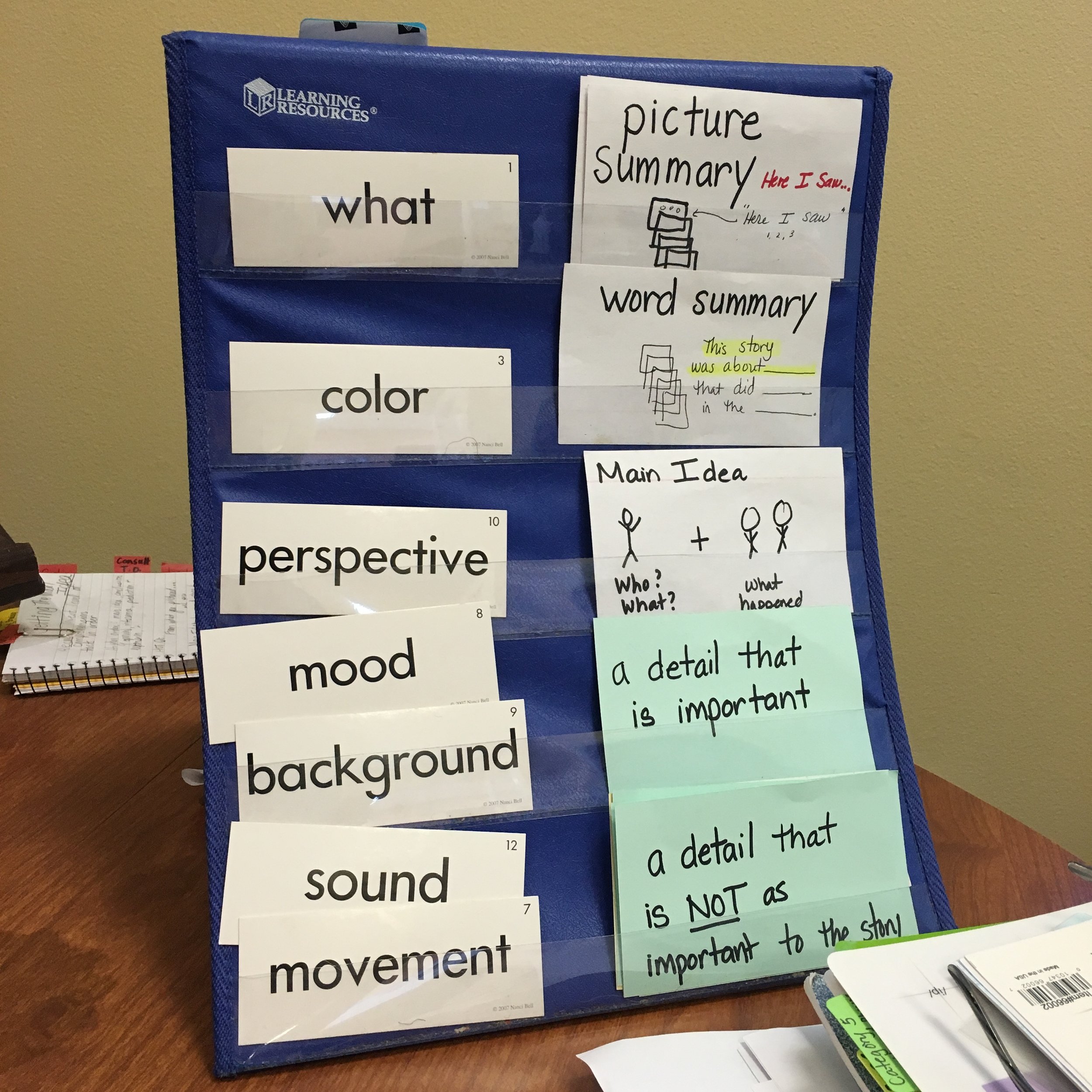

As a certified LindaMood-Bell™ clinician, I help students develop their imagery by prompting them to add color, sound, movement, perspective, and other characteristics to their pictures. They learn to verbalize a detailed summary of a short story, then hone that down to a word summary, and finally be able to tell the main idea in a single sentence. In addition to this process, I help them to identify a detail that is crucial to understanding the author’s message versus a detail that is not that important to the story. Students who struggle with visualizing while reading don't assign importance or hierarchy to the details in the text. Deciding which detail is important and which is not is key to inferring meaning in a passage or text. For example, in a story about how a sea turtle dies from eating plastic bags, is it more important that the sea turtle is as large as a horse, or that it eats jellyfish? If the student has not made a picture of a jellyfish and a picture of a plastic bag floating in the ocean, then they would not recognize their similarity and therefore not understand why a sea turtle confuses the bag for the jellyfish. With limited imagery, a student has no way to know which detail is more important.

It is a metacognitive practice to think about your own thinking. Some kids do this naturally because their brain processes information differently, and other readers need to be taught how to infer, and to think about their thinking. My one-on-one private sessions allow me to have a laser focus on this specific learning technique, making the thinking process a concrete one. Once the invisible is made visible, the student can internalize the knowledge and have it for life.